Story structure

fractals of fiction

Welcome back to class, Students of Sequel (I have more subscribers than would fit in a typical classroom, but I can imagine you all sitting in a decent-sized lecture theatre). In contrast to last week’s quite personal exploration of writing discipline, this week’s seminar is a little more theory-based, about story structure.

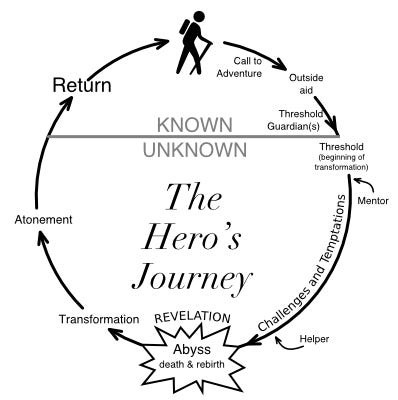

The most famous template for story structure, one that even many non-writers have heard of, is the Hero’s Journey. It started out as an attempt to describe mythological stories, but has been adapted for a much wider range of narratives, and is so well-known because of its dominance in English-language film and TV, which often follow it slavishly. The hero receives a call to adventure, usually resists it a bit, then sets off into the unknown, usually with a mentor and/or helpers. Half-way through there’s a low point for the hero (if the ending is utopic; or else, if the ending is tragic, a high point). The hero must be transformed (often redeemed, in American media, or else they must atone for a mistake) before returning to their normal life. “The hero gets what he wants, but not in the way he expected” – sound familiar? It describes at least three-quarters of the movies I’ve ever seen.

As a storyteller, what’s interesting about this quite formulaic approach is why it’s so psychologically satisfying. (The fact that it is satisfying is one of the main reasons it’s so popular in cinema, but don’t get me started about screenwriting, I’ll cover that in a later column). Does that mean you need to follow a structure like this to make a satisfying story? I don’t think so, but the fact that it will feel familiar to readers might help their enjoyment. They will readily understand how a story is unfolding, which leaves them free to think about what is unique about the story.

Another fairly well known theory of story structure develops the Aristotelian idea that a story should have a beginning, a middle and an end, into five parts:

1. Exposition (showing the protagonist’s life before everything changes, ending with the inciting incident (the call to action of the hero’s journey)

2. Rising tension, often the largest section of the story

3. The climax, where something changes

4. The aftermath (falling tension) showing what has changed

5. The resolution (in French, this is called the dénoument, which means the undoing of a knot); the ending.

This, too, is a useful guide for writers, at least writers of a story that’s intended to be a drama. The audience will expect rising tension, a climax of some kind, and something or someone, usually the protagonist, to be changed by it. This pattern of rising tension is often referred to as Freytag’s Pyramid though most modern stories have the climax close to the end, so it’s far from being a symmetrical pyramid shape.

This convention of dividing drama into five acts isn’t universally agreed, though again it is dominant in the world of English literature thanks to Shakespeare. Some plays only have three or four acts, but it’s easy to say that those are simply compressing multiple parts of the five-act structure into one section. This is the position John Yorke takes in one of my favourite books about narrative, Into The Woods (which I have briefly mentioned twice already, in part 2, What is a Novel, and part 14, about Stealing). But he takes this argument a step further, and argues that when you look inside each act, it contains a multi-step structure that follows the same pattern; and again when you go down to the scene level, the same structure applies, in that a scene will have beats patterned on the same structure: exposition (scene-setting, even if it’s just an “establishing shot”); rising tension, a climax, an aftermath, and a resolution leading into the next scene. He uses the metaphor of a fractal, where each level has its own structure derived from the structure of the next level up.

When plotting out my debut novel Parallel Lines I found this idea useful. I didn’t go out of my way to fit my plot into it, but it seemed to fit naturally all the same. Because my novel spans 11 years, I focussed in on three shorter periods within that time (at the beginning, the middle and the end), and covered what happened between those periods in two transitional sections between them: five acts. Each act tells a particular story about the protagonists, and how events changed them, so each act has a five-act structure of its own which follows what Yorke calls the “roadmap of change”, a more generalised reformulating of the hero’s journey: Act 1 (no knowledge, gaining knowledge, awakening); Act 2 (doubt, overcoming reluctance, acceptance); Act 3 (experimenting with knowledge, key knowledge, post-knowledge; Act 4 (doubt, growing reluctance, regression); and Act 5 (reawakening, re-acceptance, mastery of knowledge). This is very general, which is why it can be used to describe most stories. It’s almost inherent in stories that there is change, otherwise is it really even a story? In the case of my novel, which is a romance, the characters are challenged and changed by the changing times and by each other. In stories that are more concerned with plot than character, the characters often start off being changed by the world, and end up gaining the knowledge they need to change the world in some way. And conventionally, novels are structured into chapters each of which moves the story forward, and so is a story in its own right (literally, in the case of serial novels which were once the predominant form). Chapters tend to have a formal beginning and end, too, often in the form of a change of tone or pace, which seems to make them feel more satisfying to the reader, perhaps by giving a sense of progress through the story.

Deciding whether to expose the structure of the story to the reader, or to what extent to do this, is a choice every novelist should make consciously. Some novels don’t have chapters; others have both chapters and clearly separated sections of the story often called books or parts. I thought carefully about whether to signal the five acts of PL to the reader, and eventually decided against, feeling it would be obvious enough. Time passes between every chapter and the next, which is how I broke the story up to chapters in the first place; the fact that more time passes between each of the five parts isn’t really relevant to the story and so didn’t need drawing attention to. But for different stories, and perhaps for writers with different sensibilities or preferences, there are always alternatives. And having made this choice for the first book, I now have to decide whether to carry on the same way in the sequel, or whether the sequel should strike off in a different style. I’m still thinking about it.

That concludes this presentation about structure. Thanks for staying awake and not looking out of the window the whole time. See you next week, and if you’re enjoying Sequel Country, please tell someone about it. The button below is a handy way to do it.